April 11, 2016

Episode 46

By Giang Nguyễn

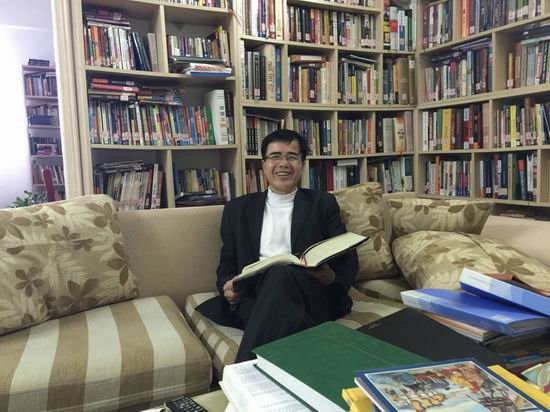

Hoàng Văn Dũng, a 36-year-old activist with the Việt Nam Path Movement, is making his way to a middle school in Sài Gòn’s Phú Nhuận District. He is dressed in a crisp white shirt and a tie. Dũng is on the campaign trail for a seat on Việt Nam’s 14th National Assembly. On this Monday night in late March, he is shaking hands with supporters.

They clap and clamor as he puts an arm around his wife and enters the school. “He’s the people’s candidate,” they cheer.

Tonight he faces his biggest hurdle in the life of his candidacy. He has to clear a majority of the votes cast at tonight’s voters’ consultation, a type of town hall with residents from his administrative ward.

But before he even gets that far, he’s stopped.

A man bars the entryway, flanked by several uniformed policemen. “Does your wife have an invitation?” he asks.

The couple eventually makes it into the meeting, after Dũng calls a representative of the organizing committee to complain.

An election controlled by a Communist front

Election-related events are organized by the Fatherland Front, an entity under the Communist Party. It works to mobilize, but more often to control, the people’s political activities. The National Assembly election takes place every five years, and the Fatherland Front holds the essential role of approving the candidate roster and organizing election procedures like this consultation.

“I was invited to the event at 7pm,” Dũng recounted to Loa.

“But the voters brought in by the officials were all already seated and had filled the room by 6:30pm, because they knew that a lot of my supporters would show up. When my friends came to the meeting hall, the authorities didn’t let them in saying they had no invitation and weren’t from my neighborhood. It’s not clear what legal basis they have for who is invited. And when my wife made it inside, they didn’t give her a ballot. She was just allowed to listen, not vote.”

There’s more political maneuvering inside, with a handful of opponents speaking up, and they are mostly opponents. At the same time, outside, a more forceful type of missile is being thrown around.

A drive-by “shooting” unique to Vietnamese politics: a motorist lobs a plastic bag filled with pungent, fermented shrimp sauce directly at the group.

Some people have since begun referring to the election as “shrimp sauce democracy”.

Nguyễn Thuý Hạnh, a human rights activist from Hà Nội, and also a self-nominated candidate worries for her candidacy, too. “I’m just waiting for something like what happened to Hoàng Văn Dũng to happen to me,” says Hạnh. “I’m waiting for the consultation in my ward.”

Hạnh and Dũng are among more than 150 contenders vying for seats in the 500-member-strong legislative body without the Communist Party’s official backing, though only about two dozen of them are doing so as an act of political dissent.

Hạnh says when she decided to run, she didn’t ask anyone’s opinion – not her family, nor her friends nor her co-workers at the sugarcane factory where she’s the director of external relations. To her surprise, they all supported her decision.

“I hope that through my candidacy, people will rethink their responsibilities towards society and towards their constitutional rights that they have ignored for some many years,” she tells Loa. “And I also hope that people won’t be apathetic or indifferent. Let’s rise up and reclaim our human rights.”

‘Democracy in Việt Nam’ launched a thousand critics

The 53-year-old says she was motivated to run in part because Nguyễn Phú Trọng, the Communist Party’s General Secretary, recently proclaimed Việt Nam a beacon of democracy.

“Our national assembly delegates were telling me that ‘This is the height of democracy.’” Trọng made the comments after he was reappointed to the country’s most powerful position during the Communist Party Congress in January. It became the phrase that launched a thousand critics and a rallying cry for those wanted to test to the limits of Việt Nam’s “democracy” and launched their own independent tickets.

Beginning with Dr. Nguyễn Quang A, a former Communist Party member now dissident, the self-nomination campaign gained momentum with activists and even celebrities declaring their own candidacies. The list includes a poet, a journalist, even a comedian.

The internet has made sharing news easier and the celebrity status of some have helped bring a lot more attention to an otherwise apathetic electorate that is usually uninterested, but forced to vote during the National Assembly elections.

For Huy Vũ, a 21-year-old engineering student from Sài Gòn, the upcoming vote on May 22 is nothing but a big rubber-stamp process.

Vũ tells Loa: “As far as the election of the party, really, why should I care? Whether I do or not, everything has already been settled. Any candidates for any position in the party that we can vote for, have already been determined ahead of time.”

But a 32-year-old teacher from Nam Định in northern Việt Nam says she became interested in this election, because her idol, celebrity singer Mai Khôi, decided to run as an independent. “These independent candidates, they’re young and enthusiastic. I’m not really sure why they are running,” she muses to Loa. “But I see that they have energy. And if they get into the upper levels of government, maybe they can do something for the young people. On Facebook, I have seen some support her, some are against. For me, I think it’s a courageous act, and I support her.”

A campaign of trials, a victory over fear

It does take a certain courage to run, in any election, anywhere in the world: to put your name out there, to expose your life’s deeds (and misdeeds) for everyone to scrutinize, and to persist against odds. In Việt Nam, it’s a feat of bravery.

Populace consultations like the one Hoàng Văn Dũng went through in Sài Gòn, have been derided as “denunciation trials” – a not too subtle reference to the disastrous public condemnations during the Communist Land Reform era in the 1950s, when sons denounced fathers and peasants denounced landowners before they were killed.

At one neighborhood town hall in Sài Gòn for independent Nguyễn Trang Nhung, the candidate emerged from her populace consultation, sobbing uncontrollably.

She appears to nearly faint as she falls into the arms of her supporters waiting outside. “It truly was a denunciation trial,” she declared in tears.

Nguyễn Thuý Hạnh, the candidate from Hà Nội, says the decision to run independently has been in itself an achievement for her: “At this point, I have already told everyone that I have won. This victory here is a victory over my own fear. If something happens to me, then it’s the Communist Party that has tainted itself”.

Election rules require that each candidate must pass through several steps and consultations organized by the Fatherland Front before they are added to the final candidate roster. The law, if it is observed right, should provide a shield for candidates and activists, says Hạnh.

“I think this process of running for a seat in the Assembly is a method of nonviolent action that can attract many concerned people, and people see it as a safe method. That’s why people are paying attention and are so supportive. I think this is a great way to resist. For our supporters, when we go out and protest China, or do anything else, they are afraid. But when we run for the National Assembly, clearly we are following the law, the constitution, in a peaceful way. People don’t see it as dangerous, so they’re happy to support me and campaign for me. This is a really great way to attract those people who are still on the fence, who are still afraid.”

An undemocratic election: the stage for a refusal to vote

As for Dũng, he says he was never under any illusion that this process was democratic, though he believed he could make it all the way to May 22.

Despite having been disqualified at his consultation meeting, he tells Loa he’s never been happier.

“Everybody understands that there’s no democracy with the Communist Party organizing this election. But compared to previous elections, I see concrete differences, concrete progress in the way they’re getting constituents’ opinions. First, I could express my opinion, even though the authorities tried to stop me. Second, the constituents didn’t express any criticism against me and in the end, the government had to use people on the inside, those in power in the municipal ward, to express opinions critical of me, in order to sway the people. But in previous years, they could just rely on ordinary people to do that for them.”

Human rights lawyer Lê Quốc Quân was one of the lone individuals who attempted to run as an independent in 2011 but was disqualified. The former prisoner of conscience says that although the probability that any of these dissident candidates make it on the final ballot or even through to the National Assembly is zero but they have played a critical role in this so-called election.

“The Vietnamese government always claims it is a democratic government and many people in Việt Nam still believe what the Communist Party tells them,” says Quân.

“When these independents run for office, they are evidence for everyone to see how the Communist Party is violating the rules of democracy. Thus they are a proof that Việt Nam has no democracy. And once the people know the truth and that this is a lack of democracy, they can take the next step and refuse to vote. They can say, my ballot has no meaning. And they can deny their vote.”

Dũng says he plans to do just that. Now no longer a candidate, he says he plans to educate average voters to understand the value of their ballot.

Will he stand again as a candidate in the next National Assembly election, five years from now?

“I will definitely continue to stand for election. But I don’t think it’ll be another five years,” Dũng asserts. “There will be another, new election. And it will be an election that the people will rejoice to participate.”

*Editor’s note: By the airing of this episode, most independent candidates have been disqualified at the consultation stage, while some have boycotted the voters’ consultations due to a lack of transparency.

Source: Loa